-

LaSalle’s Brian Klinksiek and Ryan Daily (L-R) discuss the latest on purpose-built student accommodation (PBSA) in Europe and beyond. Purpose-built student accommodation (PBSA) in Europe ranks as one of our top-conviction sectors for investment in the coming years. No longer deserving of the “niche” label in the United Kingdom, it is already more institutional than any other type of living sectors property in the country and is rapidly maturing in Continental Europe as well. The rise of student accommodation on investors’ buy lists is for good reason. This ISA Briefing will set out why that is so and discuss how the sector stands out in Europe compared with student housing in the rest of the world.

Demand factors

After a brief, pandemic-induced interruption, in-person learning in Europe is back with more students enrolled than at any point in history. Higher education participation rates in the European Union have steadily risen across recent years, reaching an all-time high of 36% for 20-24 year-olds1 in 2021/22, with the same proportion recorded for the UK in 2023.2 A total of 18.5 million students were studying in the EU as of the 2021/22 academic year, with a further 2.9 million in the UK, having grown by 8% and 20%, respectively, over the previous five years.3

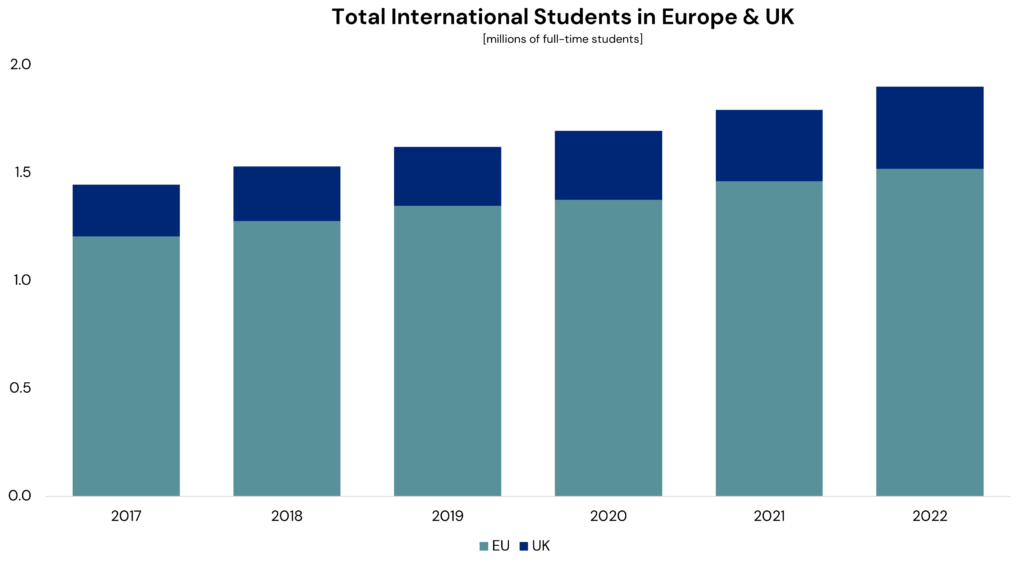

Demand for PBSA varies by profile of student. While domestic students are still crucial as a source of demand, particularly in markets where few students commute from home to study, international students are far more likely to reside in PBSA than domestic students (60% more likely to do so in the UK, as an example4). As shown in the chart below, international student mobility has been on a clear growth trend in recent years, with 2021/22 seeing a record number of foreign students in the EU and UK. European students studying outside their home countries elsewhere in Europe is a longstanding feature of the market, facilitated by freedom of movement within the EU, well-established student exchange programs, the rise of English-language courses and Europe’s dense geography.

A key driver of growth has been students from outside Europe. Europe has an outsized number of highly ranked universities relative to its size,5 a prevalence of English-language courses (which are increasingly no longer limited to the UK and Ireland) at a comparatively cheaper cost of tuition and living compared to North America.6 These attributes taken together can explain the sharp rise in non-EU students studying in the bloc, whose numbers have grown 31% since 2016.7 In the UK, the growth has been even faster, at 59% over the same period.8

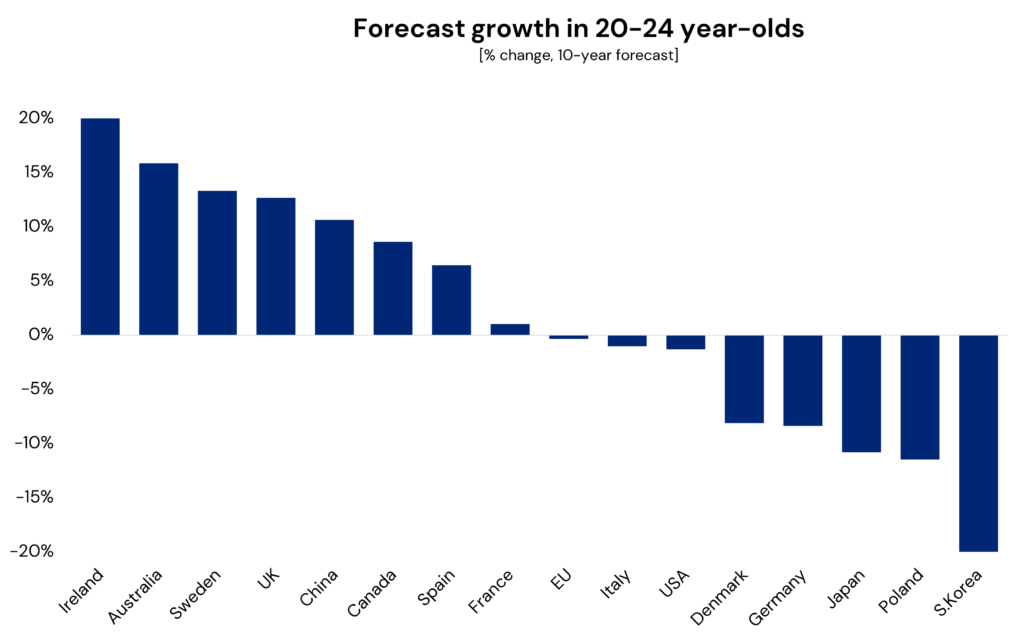

That said, there are demand-side risks to be mindful of. The demographic outlook for Europe is mixed; forecasts for some countries such as the UK, Spain and Sweden show a demographic ‘bump,’ with the number of university-aged people growing ahead of national population levels. However, in other nations, numbers are forecast to be broadly flat (France) or negative (Germany and the Netherlands). This suggests uneven growth in demand for higher education going forward.9

This mixed demographic outlook will mean greater reliance on international student demand, but there are tentative signs that may also be facing some headwinds. A recent policy change in the UK has removed the right to visas for international students’ family members.10 For now, this change represents tinkering around the edges and is unlikely to have a major impact on demand. It does, however, indicate a directional change in policy aimed at restricting overseas student numbers, presumably in a bid to bring down immigration figures. Such policy changes may incrementally dissuade would-be foreign students from studying in the UK, though demand may shift elsewhere, potentially to the benefit of other European countries. Despite such risk factors, the overriding view is one of positivity for higher education demand in Europe and therefore PBSA.

Supply factors

European student housing should be viewed within the wider context of the region’s housing market. Europe is currently facing a long-term, persistent housing shortage. Housing scarcity is not limited to major gateway cities, but is also the reality within mid-sized cities and even smaller university towns. Since 2010, Europe has built homes at a rate only 40% below pre-GFC levels,11 contributing to rising rents, increasing house-price-to-income ratios and worsening access to suitable housing. Demand for rental housing in cities remains robust, supported by long-term trends of immigration, urbanization and declining home ownership rates; as such, the imbalance between supply and demand is now fully entrenched.12Students are, like all participants in the housing market, at the mercy of housing supply and demand. Shortages have fed through to the student market, with students finding accommodation increasingly unaffordable. Over the past two years, this has led to sharp growth in PBSA rents, with several UK cities reporting year-over-year growth in the high teens for 2023, and other markets experiencing growth well ahead of previous levels.13 The lack of supply is also leading to students being housed increasingly in unsuitable conditions; stories from the UK of students living in hotels or in completely different cities over an hour travel from campus are a clear symptom of insufficient student housing stock.

New investment in the sector should contribute to resolving the imbalance, but it will be a major challenge to fully close the wide gap between supply and demand. While there are nuances between markets, rising construction and development financing costs are making the delivery of new schemes less economical, evidenced by a sharp decline in the number of residential permits issued in several countries over the past year.14 Furthermore, restrictive planning laws and burdensome safety regulations are lengthening the time it takes for projects to be realized.

These factors inform our positive outlook on the rental housing market in Europe, which carries over into PBSA. The imbalance between supply and demand will likely persist and even worsen, driving very low vacancy and supporting strong rental growth for owners of residential and student housing real estate, or those who can deliver new schemes in those sectors.

Regulation haven

Regulations in Europe can act as a handbrake for residential rents, as we set out in our ISA Briefing, Controlling Interest: Keeping tabs on residential regulations. In nearly all continental European rental markets, rents cannot be increased annually at the landlord’s discretion, with rental levels for in-place tenants typically linked to a backward-looking index. During the recent ‘great reflation’ period, this has meant income from many rented residential properties did not keep pace with inflation. But student housing stands out from more traditional rental housing investments as having a cash flow profile far less impacted by the growth-muting tendencies of regulation.In part, this is because PBSA often faces less regulation or stands outside of regulatory systems altogether. Students’ nature as transient, temporary residents means that their needs are rarely prioritized by local politicians, particularly compared to those of permanent residents. They typically only stay in a city for a few years, do not have dependents and their rental obligations often come with implicit or explicit parental guarantees. This means that PBSA is targeted for rent controls far less often than the wider rental market. Moreover, zoning and classifications for student accommodation are often distinct from standard rental housing, exempting it from regulations that limit absolute rent levels or restrict annual rental increases. Moreover, regulatory requirements on minimum unit sizes or lease lengths usually do not apply.

Even where regulated, PBSA benefits from its relatively short duration of tenancy. Given the vast majority of students study for 3-4 years, there is far greater annual turnover of tenants compared with the wider residential market. Faster turnover allows for landlords to more effectively mark rents to market levels. This means PBSA rents may better keep pace with inflation, even in jurisdictions where regulations do apply to the sector.

Increasingly mature

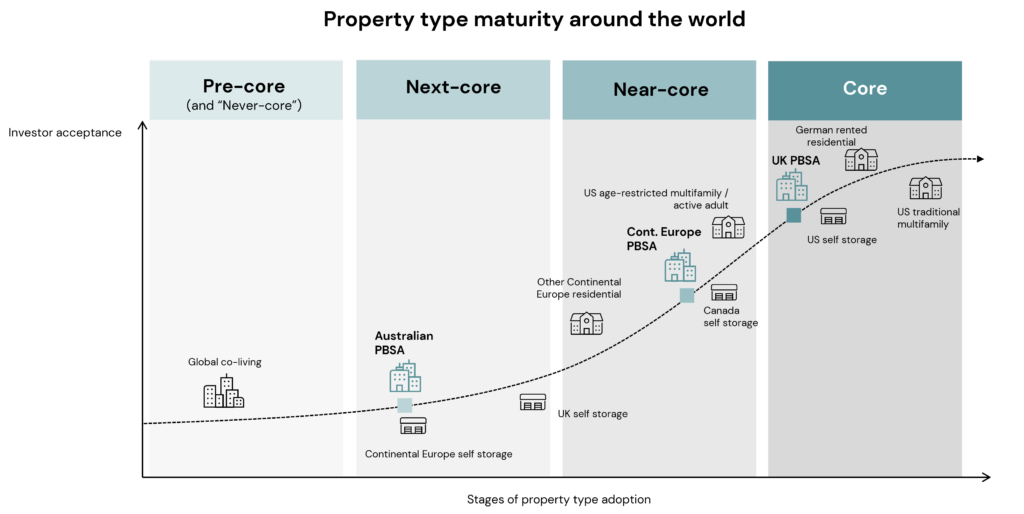

The increased maturity of student accommodation is another factor in its favor. The UK is clearly ahead of the rest of Europe in this regard, with a deep, liquid investment market, publicly traded REITs and a large number of established specialist operators. The sector’s wide acceptance from both tenants and investors means that we would consider it a ‘Core’ sector on our ‘going mainstream’ framework, as detailed in our ISA Portfolio View. Elsewhere in Europe the sector is considered more niche, but its growing acceptance means we would consider it ‘Near-Core’ on the same framework. Investment figures support the observation of a varying level of maturity for the sector—UK PBSA has made up 66% of investment volumes annual on average since 2014, despite the EU having 6.4 times the number of students.15

Over time, we expect this to change; the opportunity for investors to take advantage of the structural trends outlined above is likely to drive increased investment in the sector. Countries like as Spain or Italy have PBSA provision rates16 of below 10%, compared to more than 30% in some major UK markets,17 suggesting there is significant scope for delivery of new supply. Cities such as Milan, Madrid and Barcelona all have student populations of over 100,000 and multiple well-ranked institutions, giving them diverse demand bases and making them likely to be key growth markets for the sector in the coming years.

As niche sectors mature, greater liquidity and investor acceptance tends to lead to any yield premium they offer versus traditional sectors narrowing, as investors require less compensation for liquidity and transparency risks; such a pattern has already been observed in UK PBSA. This potential narrowing of yields in European markets is another factor behind our conviction that the sector is likely to offer attractive returns.

Comparisons with other regions

Student accommodation in much of Asia Pacific is still in a nascent stage, with relatively limited PBSA stock, few specialized operators and comparatively little institutional investment. The major exception in the region is Australia, which has characteristics similar to those of the sector in Europe and the UK, but is a number of years behind in its evolution. This suggests a similar path to maturity may lie ahead. Like Europe, Australia benefits from English-language courses at comparatively lower tuition costs than the US, while also offering post-study work visas. As a result, it has an even higher proportion of international students than most major European countries.18 Still, the Australian PBSA sector remains in its infancy as an investable property type. Stock numbers are low even compared to the most immature countries in Europe, with a student-to-bed ratios of 16-to-119 and significantly higher than the UK where it is around 3-to-1.Traditionally, international students in Australia tap into private rental housing for accommodation. Both the private rental market and the PBSA sector in Australia have experienced tight occupier market fundamentals and experienced double-digit rental growth over the past two years.20 The solid performance has been primarily driven by strong migrant inflows, including international students, as well as high interest rates that encourage Australians to rent rather than buy, and relatively limited existing stock and new supply of all types of housing.

The United States, by contrast, has a more established student housing sector, but our view of the property type there is less favorable as compared to other regions. For a start, the demographics are less favorable given the population of 18-to-24 year-olds in the US is forecast to decline through 203321 and enrollment rates at 4-year institutions have remained roughly flat since 2010.22

An additional point of difference between US and European universities is their locations. Many top-tier US universities are in small cities in which a single school dominates the population and economy. Student housing properties in these markets are dependent on a single source of demand that controls enrollment growth and housing policy. Additionally, barriers to new supply are generally lower compared to major European cities, which allows for more new development to come in and disrupt the market. Taken together, these factors mean rent trends in these markets can be volatile. While there are similar university-centric towns in Europe, our investment focus is on the larger markets, where housing markets are tightest and there is a diverse demand base from multiple universities.

Looking ahead

- Europe’s leading universities should continue to attract demand from students, both domestic and international, positioning student housing for further growth. However, this growth may be uneven given mixed demographic outlooks and the potential for government interference. Investors should focus on the most-supply constrained markets, where there are resilient and varied sources of demand from multiple universities.

- European PBSA can act as a proxy for investment in the housing markets of supply constrained cities that face regulation, while generating cashflows more akin to investments in unregulated markets. We maintain our previously stated view that residential regulations can lead to lower cash flow volatility and thus may even mean better risk-adjusted returns. However, given the persistent housing shortages and continued demand for rental housing of all forms, we forecast rental growth across many European residential markets to be well ahead of inflation. This means in markets where residential landlords are constrained by inflationary indexation, owning PBSA may give investors a better opportunity to capture that market growth than does traditional residential.

- Elsewhere in the world, the investment case for student accommodation is less compelling. The US market, for example, is characterized by a relatively weak demographic profile for student demand. Moreover, in many cases investing in it involves exposure to smaller cities to which investors would not otherwise seek exposure. That said, PBSA markets with similar characteristics to Europe, such as Australia, can offer interesting opportunities for global investors. For investors seeking higher returns, entry into sectors can be especially interesting when they are at the early stages of their emergence.

Footnotes1 Source: Eurostat

2 Source: Higher Education Statistics Agency (UK)

3 Source: Eurostat, Higher Education Statistics Agency (UK)

4 Source: Savills

5 The number of European universities in the top 2000 spots Center for World University Rankings (CWUR) league tables per capita is the highest of any world region, according to data from CWUR, Oxford Economics, and analysis by LaSalle.

6 Source: Educationdata.org

7 Source: Eurostat

8 Source: HESA

9 Assuming no change in the propensity of people in that age cohort to attend university.

10 UK Government introduced policy on January 1st 2024

11 Source: European Central Bank

12 For deeper analysis of European housing markets and the underlying supply imbalance see LaSalle’s ISA Outlook 2024.

13 Source: JLL

14 LaSalle analysis of data taken from the national statistics agencies of major European countries (Germany, UK, France, Spain, Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Italy, Portugal, Netherlands, Ireland)

15 Source: MSCI Real Capital Analytics

16 Metric defined as number of purpose-built student beds as a share of total enrolled population of students in higher education.

17 Source: JLL

18 Source: UNESCO

19 Source: CBRE

20 Source: SQM Research (for private rental market), as of November 2023; CBRE (for PBSA), as of August 2023

21 Source: Oxford Economics

22 Source: National Center for Education Statistics (US)

Important Notice and DisclaimerThis publication does not constitute an offer to sell, or the solicitation of an offer to buy, any securities or any interests in any investment products advised by, or the advisory services of, LaSalle Investment Management (together with its global investment advisory affiliates, “LaSalle”). This publication has been prepared without regard to the specific investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of recipients and under no circumstances is this publication on its own intended to be, or serve as, investment advice. The discussions set forth in this publication are intended for informational purposes only, do not constitute investment advice and are subject to correction, completion and amendment without notice. Further, nothing herein constitutes legal or tax advice. Prior to making any investment, an investor should consult with its own investment, accounting, legal and tax advisers to independently evaluate the risks, consequences and suitability of that investment.

LaSalle has taken reasonable care to ensure that the information contained in this publication is accurate and has been obtained from reliable sources. Any opinions, forecasts, projections or other statements that are made in this publication are forward-looking statements. Although LaSalle believes that the expectations reflected in such forward-looking statements are reasonable, they do involve a number of assumptions, risks and uncertainties. Accordingly, LaSalle does not make any express or implied representation or warranty, and no responsibility is accepted with respect to the adequacy, accuracy, completeness or reasonableness of the facts, opinions, estimates, forecasts, or other information set out in this publication or any further information, written or oral notice, or other document at any time supplied in connection with this publication. LaSalle does not undertake and is under no obligation to update or keep current the information or content contained in this publication for future events. LaSalle does not accept any liability in negligence or otherwise for any loss or damage suffered by any party resulting from reliance on this publication and nothing contained herein shall be relied upon as a promise or guarantee regarding any future events or performance.

By accepting receipt of this publication, the recipient agrees not to distribute, offer or sell this publication or copies of it and agrees not to make use of the publication other than for its own general information purposes.

Copyright © LaSalle Investment Management 2024. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced by any means, whether graphically, electronically, mechanically or otherwise howsoever, including without limitation photocopying and recording on magnetic tape, or included in any information store and/or retrieval system without prior written permission of LaSalle Investment Management.

Oct 21, 2024

Finding opportunities in European real estate debt

Dave White and Dominic Silman discuss how we identify opportunities, where we are likely to invest, and the evolving market.